General Matrix-Matrix Multiplication with Tile Library¶

Warning

This document is still experimental and may be incomplete. Suggestions and improvements are highly encouraged—please submit a PR!

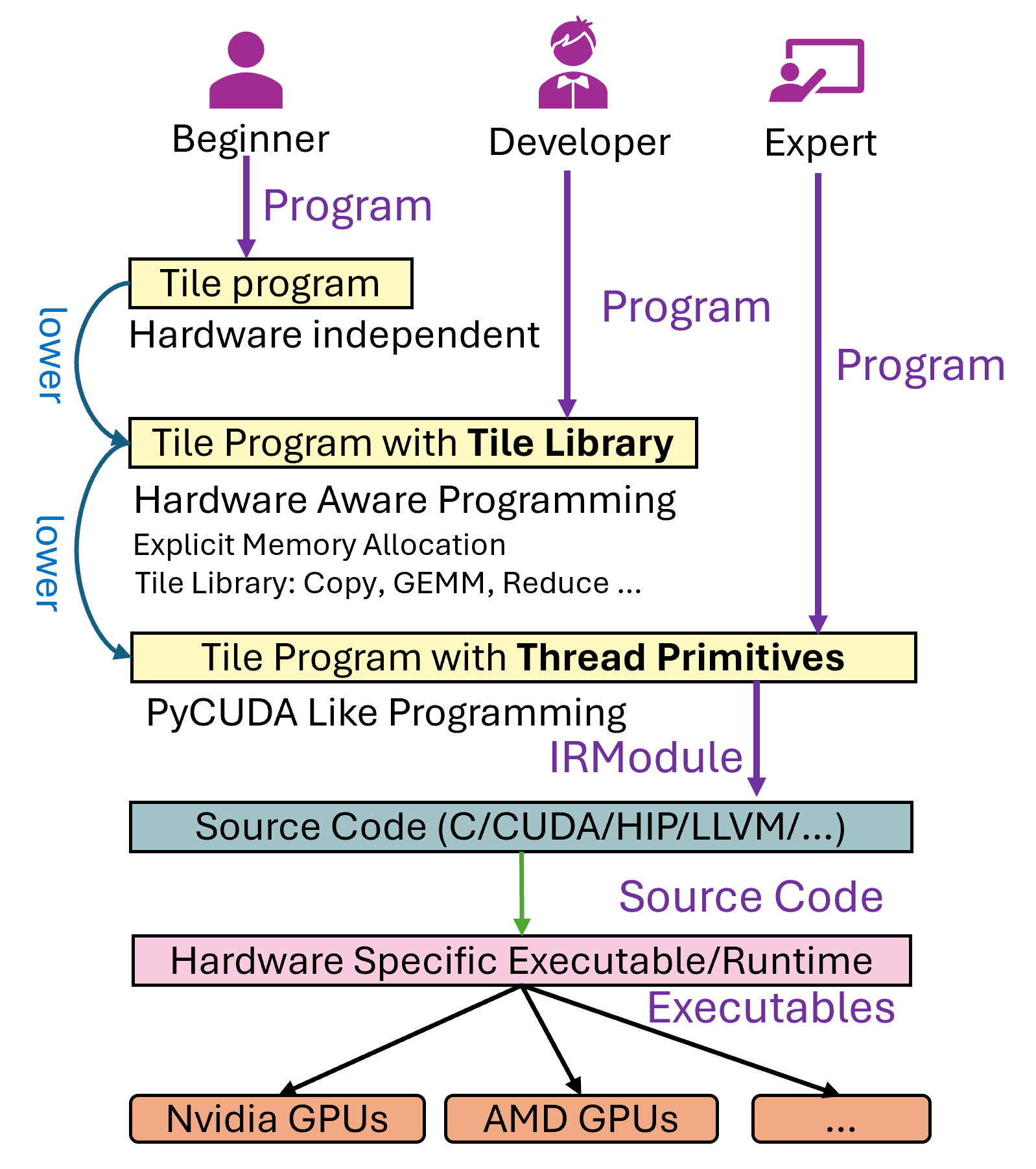

TileLang is a domain-specific language (DSL) designed for writing high-performance GPU kernels. It provides three main levels of abstraction:

Level 1: A user writes pure compute logic without knowledge of or concern for hardware details (e.g., GPU caches, tiling, etc.). The compiler or runtime performs automatic scheduling and optimization. This level is conceptually similar to the idea behind TVM.

Level 2: A user is aware of GPU architecture concepts—such as shared memory, tiling, and thread blocks—but does not necessarily want to drop down to the lowest level of explicit thread control. This mode is somewhat comparable to Triton’s programming model, where you can write tile-level operations and let the compiler do layout inference, pipelining, etc.

Level 3: A user takes full control of thread-level primitives and can write code that is almost as explicit as a hand-written CUDA/HIP kernel. This is useful for performance experts who need to manage every detail, such as PTX inline assembly, explicit thread behavior, etc.

Figure 1: High-level overview of the TileLang compilation flow.¶

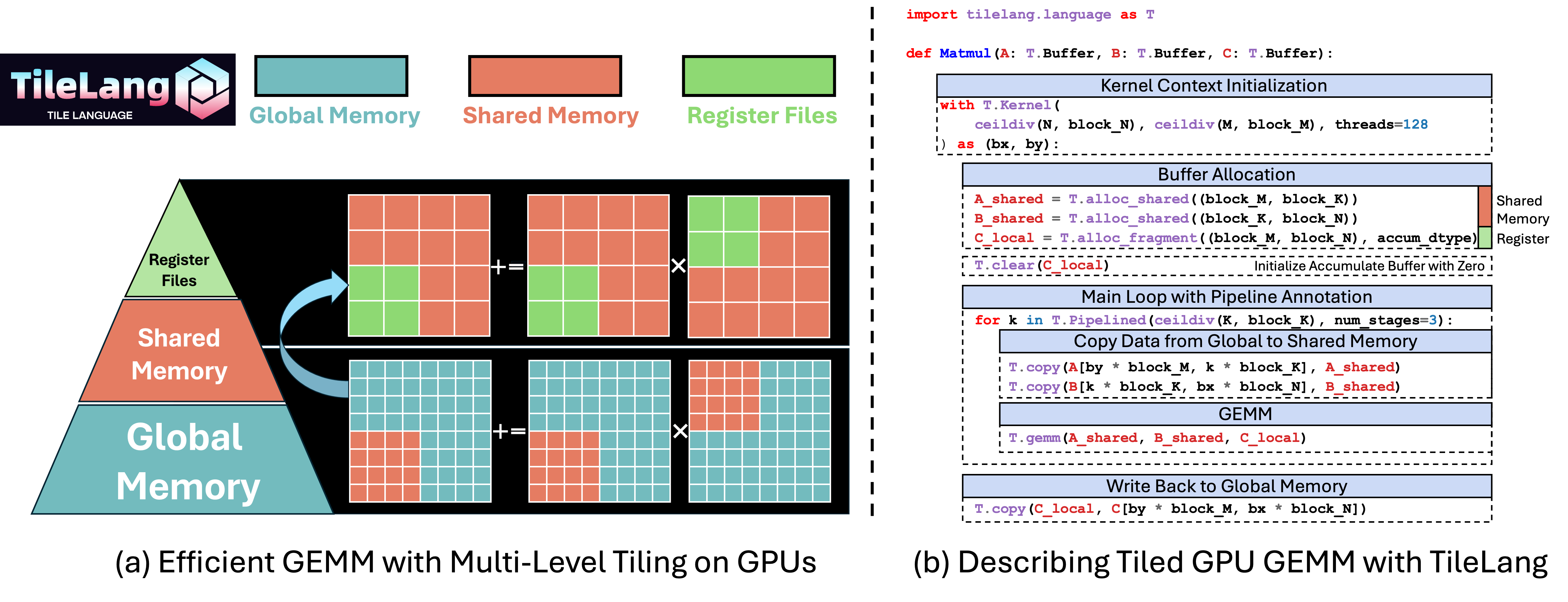

In this tutorial, we introduce Level 2 with a matrix multiplication example in TileLang. We will walk through how to allocate shared memory, set up thread blocks, perform parallel copying, pipeline the computation, and invoke the tile-level GEMM intrinsic. We will then show how to compile and run the kernel in Python, comparing results and measuring performance.

Why Another GPU DSL?¶

TileLang emerged from the need for a DSL that:

Balances high-level expressiveness (like TVM or Triton) with enough flexibility to control finer details when needed.

Supports efficient code generation and scheduling for diverse hardware backends (NVIDIA GPUs, AMD GPUs, CPU, etc.).

Simplifies scheduling and memory pipelines with built-in primitives (such as

T.Pipelined,T.Parallel,T.gemm), yet retains options for expert-level tuning.

While Level 1 in TileLang can be very comfortable for general users—since it requires no scheduling or hardware-specific knowledge—it can incur longer auto-tuning times and may not handle some complex kernel fusion patterns (e.g., Flash Attention) as easily. Level 3 gives you full control but demands more effort, similar to writing raw CUDA/HIP kernels. Level 2 thus strikes a balance for users who want to write portable and reasonably concise code while expressing important architectural hints.

Matrix Multiplication Example¶

Basic Structure¶

Below is a simplified code snippet for a 1024 x 1024 x 1024 matrix multiplication. It uses:

T.Kernel(...)to initialize the thread block configuration (grid dimensions, block size, etc.).T.alloc_shared(...)to allocate GPU shared memory.T.alloc_fragment(...)to allocate a register fragment for accumulation.T.Pipelined(...)to express software pipelining across the K dimension.T.Parallel(...)to parallelize data copy loops.T.gemm(...)to perform tile-level GEMM operations (which map to the appropriate backends, such as MMA instructions on NVIDIA GPUs).

import tilelang

import tilelang.language as T

from tilelang.intrinsics import make_mma_swizzle_layout

def matmul(M, N, K, block_M, block_N, block_K, dtype="float16", accum_dtype="float"):

@T.prim_func

def main(

A: T.Tensor((M, K), dtype),

B: T.Tensor((K, N), dtype),

C: T.Tensor((M, N), dtype),

):

# Initialize Kernel Context

with T.Kernel(T.ceildiv(N, block_N), T.ceildiv(M, block_M), threads=128) as (bx, by):

A_shared = T.alloc_shared((block_M, block_K), dtype)

B_shared = T.alloc_shared((block_K, block_N), dtype)

C_local = T.alloc_fragment((block_M, block_N), accum_dtype)

# Optional layout hints (commented out by default)

# T.annotate_layout({

# A_shared: make_mma_swizzle_layout(A_shared),

# B_shared: make_mma_swizzle_layout(B_shared),

# })

# Optional: Enabling swizzle-based rasterization

# T.use_swizzle(panel_size=10, enable=True)

# Clear local accumulation

T.clear(C_local)

for ko in T.Pipelined(T.ceildiv(K, block_K), num_stages=3):

# Copy tile of A from global to shared memory

T.copy(A[by * block_M, ko * block_K], A_shared)

# Parallel copy tile of B from global to shared memory

for k, j in T.Parallel(block_K, block_N):

B_shared[k, j] = B[ko * block_K + k, bx * block_N + j]

# Perform a tile-level GEMM

T.gemm(A_shared, B_shared, C_local)

# Copy result from local (register fragment) to global memory

T.copy(C_local, C[by * block_M, bx * block_N])

return main

# 1. Create the TileLang function

func = matmul(1024, 1024, 1024, 128, 128, 32)

# 2. JIT-compile the kernel for NVIDIA GPU

jit_kernel = tilelang.compile(func, out_idx=[2], target="cuda")

import torch

# 3. Prepare input tensors in PyTorch

a = torch.randn(1024, 1024, device="cuda", dtype=torch.float16)

b = torch.randn(1024, 1024, device="cuda", dtype=torch.float16)

# 4. Invoke the JIT-compiled kernel

c = jit_kernel(a, b)

ref_c = a @ b

# 5. Validate correctness

torch.testing.assert_close(c, ref_c, rtol=1e-2, atol=1e-2)

print("Kernel output matches PyTorch reference.")

# 6. Inspect generated CUDA code (optional)

cuda_source = jit_kernel.get_kernel_source()

print("Generated CUDA kernel:\n", cuda_source)

# 7. Profile performance

profiler = jit_kernel.get_profiler()

latency = profiler.do_bench()

print(f"Latency: {latency} ms")

Key Concepts¶

Kernel Context:

with T.Kernel(T.ceildiv(N, block_N), T.ceildiv(M, block_M), threads=128) as (bx, by):

...

This sets up the block grid dimensions based on N/block_N and M/block_M.

threads=128specifies that each thread block uses 128 threads. The compiler will infer how loops map to these threads.

Shared & Fragment Memory:

A_shared = T.alloc_shared((block_M, block_K), dtype)

B_shared = T.alloc_shared((block_K, block_N), dtype)

C_local = T.alloc_fragment((block_M, block_N), accum_dtype)

T.alloc_sharedallocates shared memory across the entire thread block.T.alloc_fragmentallocates register space for local accumulation. Though it is written as(block_M, block_N), the compiler’s layout inference assigns slices of this space to each thread.

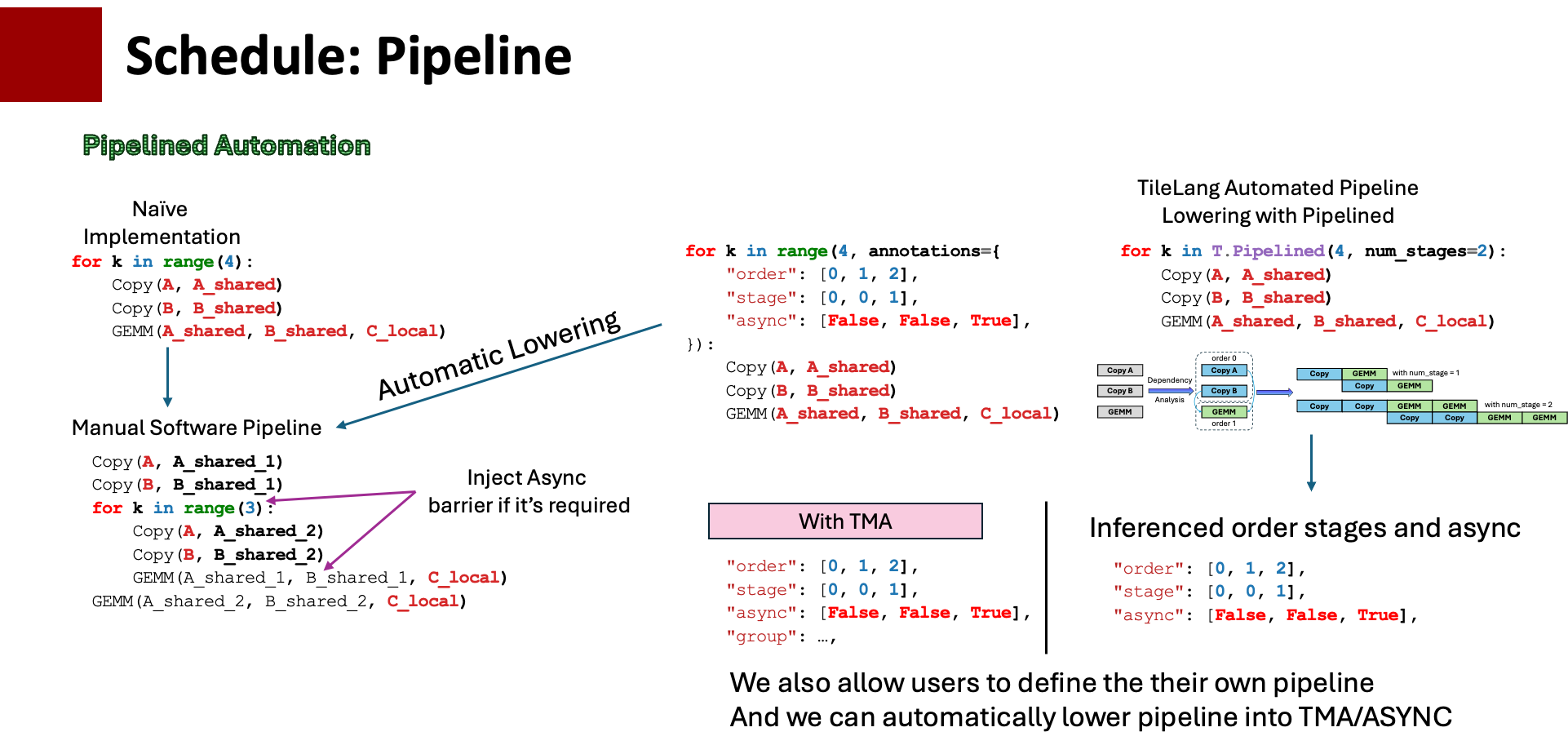

Software Pipelining:

for ko in T.Pipelined(T.ceildiv(K, block_K), num_stages=3):

...

T.Pipelinedautomatically arranges asynchronous copy and compute instructions to overlap memory operations with arithmetic.The argument

num_stages=3indicates the pipeline depth.

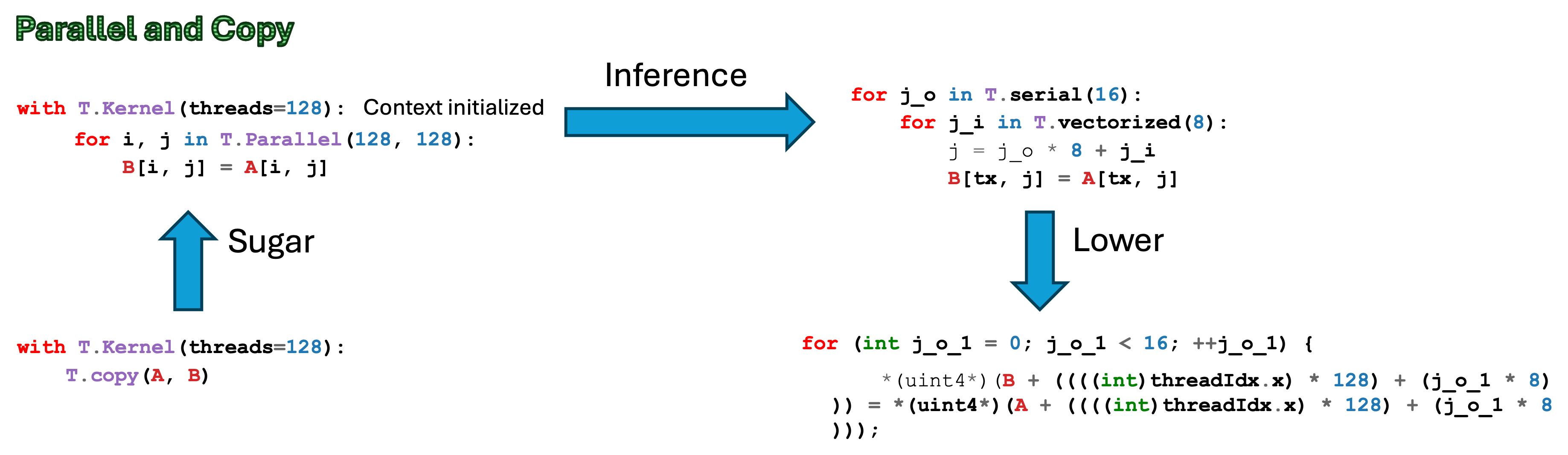

Parallel Copy:

for k, j in T.Parallel(block_K, block_N):

B_shared[k, j] = B[ko * block_K + k, bx * block_N + j]

T.Parallelmarks the loop for thread-level parallelization.The compiler will map these loops to the available threads in the block.

Tile-Level GEMM:

T.gemm(A_shared, B_shared, C_local)

A single call that performs a tile-level matrix multiplication using the specified buffers.

Under the hood, for NVIDIA targets, it can use CUTLASS/Cute or WMMA instructions. On AMD GPUs, TileLang uses a separate HIP or composable kernel approach.

Copying Back Results:

T.copy(C_local, C[by * block_M, bx * block_N])

After computation, data in the local register fragment is written back to global memory.

Comparison with Other DSLs¶

TileLang Level 2 is conceptually similar to Triton in that the user can control tiling and parallelization, while letting the compiler handle many low-level details. However, TileLang also:

Allows explicit memory layout annotations (e.g.

make_mma_swizzle_layout).Supports a flexible pipeline pass (

T.Pipelined) that can be automatically inferred or manually defined.Enables mixing different levels in a single program—for example, you can write some parts of your kernel in Level 3 (thread primitives) for fine-grained PTX/inline-assembly and keep the rest in Level 2.

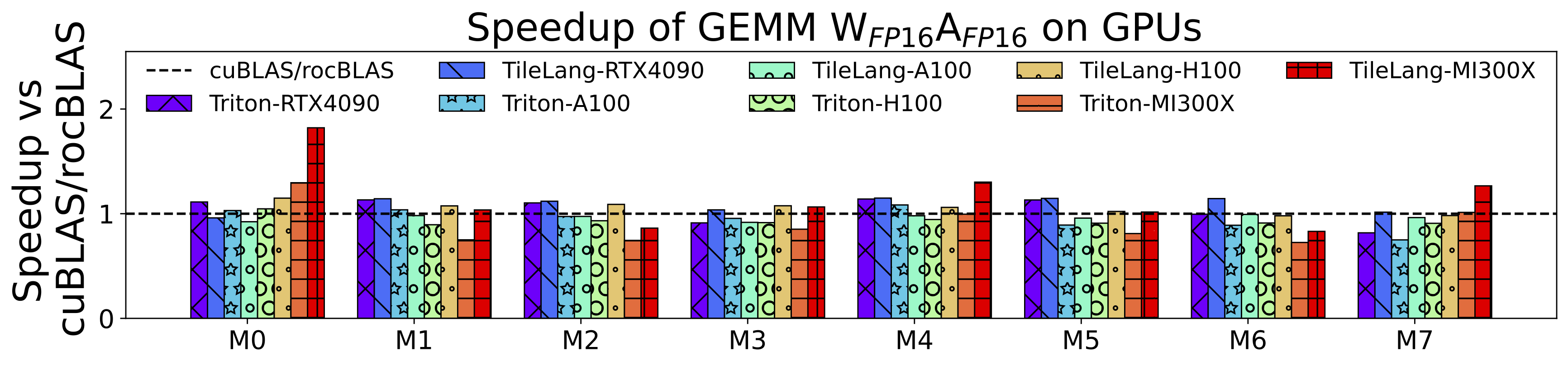

Performance on Different Platforms¶

When appropriately tuned (e.g., by using an auto-tuner), TileLang achieves performance comparable to or better than vendor libraries and Triton on various GPUs. In internal benchmarks, for an FP16 matrix multiply (e.g., 4090, A100, H100, MI300X), TileLang has shown:

~1.1x speedup over cuBLAS on RTX 4090

~0.97x on A100 (on par with cuBLAS)

~1.0x on H100

~1.04x on MI300X

Compared to Triton, speedups range from 1.08x to 1.25x depending on the hardware.

These measurements will vary based on tile sizes, pipeline stages, and the hardware’s capabilities.

Conclusion¶

This tutorial demonstrated a Level 2 TileLang kernel for matrix multiplication. With just a few lines of code:

We allocated shared memory and register fragments.

We pipelined the loading and computation along the K dimension.

We used parallel copying to efficiently load tiles from global memory.

We invoked

T.gemmto dispatch a tile-level matrix multiply.We verified correctness against PyTorch and examined performance.

By balancing high-level abstractions (like T.copy, T.Pipelined, T.gemm) with the ability to annotate layouts or drop to thread primitives (Level 3) when needed, TileLang can be both user-friendly and highly tunable. We encourage you to experiment with tile sizes, pipeline depths, or explicit scheduling to see how performance scales across different GPUs.

For more advanced usage—including partial lowering, explicitly controlling thread primitives, or using inline assembly—you can explore Level 3. Meanwhile, for purely functional expressions and high-level scheduling auto-tuning, consider Level 1.