🚀 Write High Performance FlashMLA with TileLang on Hopper¶

TileLang is a user-friendly AI programming language that significantly lowers the barrier to kernel programming, helping users quickly build customized operators. However, users still need to master certain programming techniques to better leverage TileLang’s powerful capabilities. Here, we’ll use MLA as an example to demonstrate how to write high-performance kernels with TileLang.

Introduction to MLA¶

DeepSeek’s MLA (Multi-Head Latent Attention) is a novel attention mechanism known for its hardware efficiency and significant improvements in model inference speed. Several deep learning compilers (such as Triton) and libraries (such as FlashInfer) have developed their own implementations of MLA. In February 2025, FlashMLA was open-sourced on GitHub. FlashMLA utilizes CUTLASS templates and incorporates optimization techniques from FlashAttention, achieving impressive performance.

Benchmark Results¶

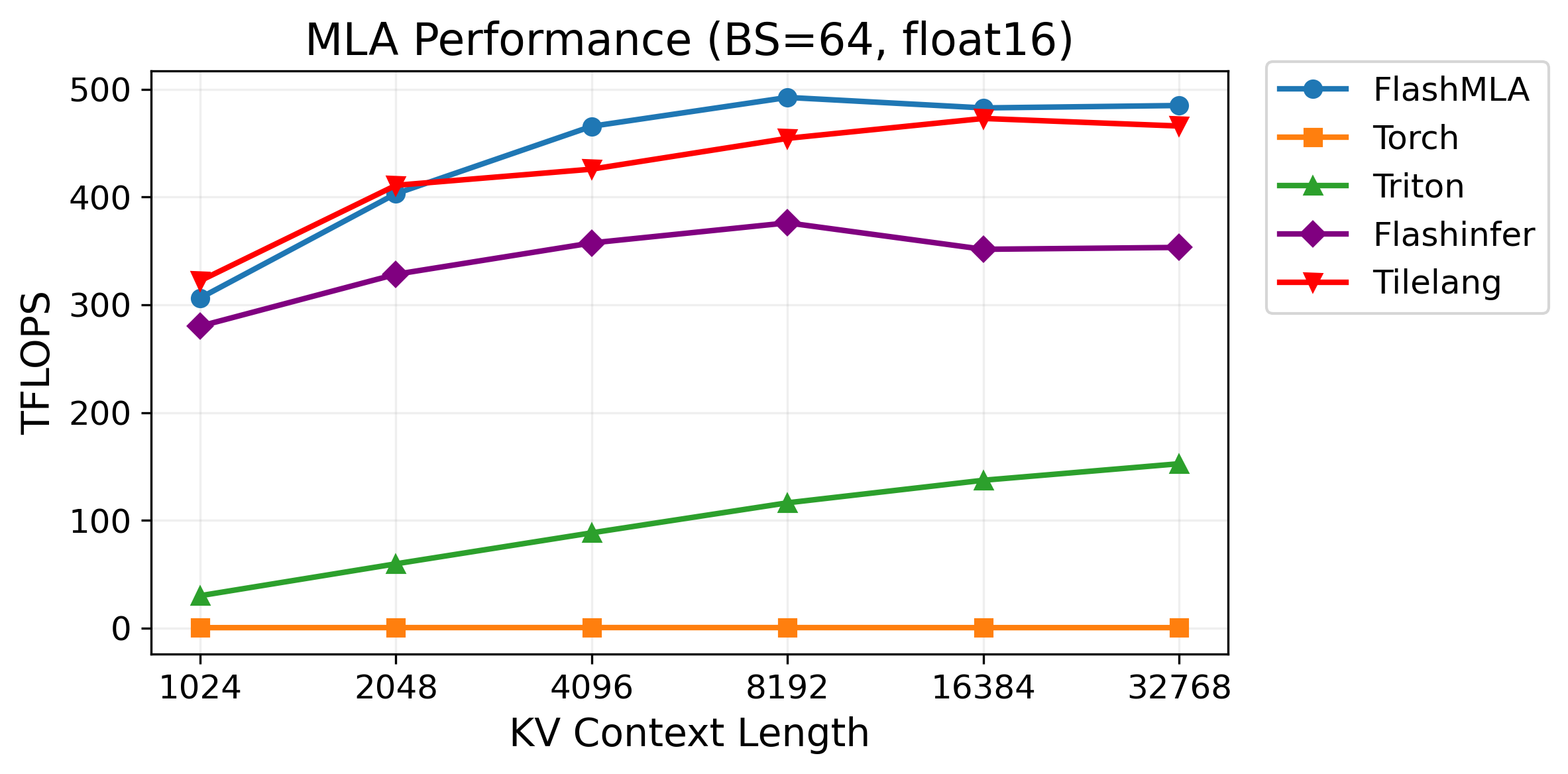

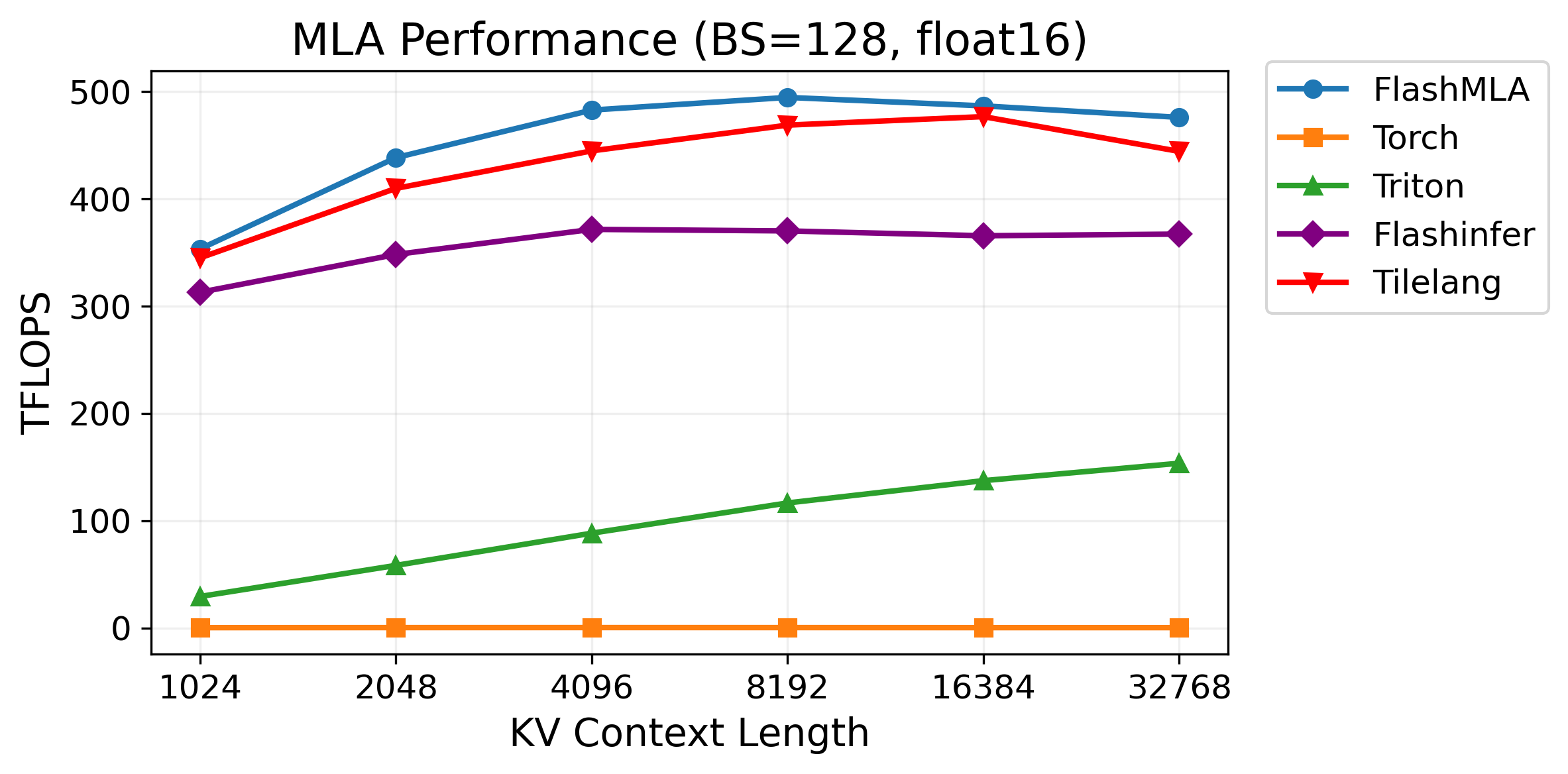

We benchmarked the performance of FlashMLA, TileLang, Torch, Triton, and FlashInfer under batch sizes of 64 and 128, with float16 data type, as shown in the figures below.

Figure 1: Performance under batch size=64¶

Figure 2: Performance under batch size=128¶

As shown in the results, TileLang achieves performance comparable to FlashMLA in most cases, significantly outperforming both FlashInfer and Triton. Notably, TileLang accomplishes this with just around 80 lines of Python code, demonstrating its exceptional ease of use and efficiency. Let’s dive in and see how TileLang achieves this.

Implementation¶

First, let’s review the core computation logic of traditional FlashAttention:

# acc_s: [block_M, block_N]

# scores_max: [block_M]

# scores_scale: [block_M]

# acc_o: [block_M, dim]

for i in range(loop_range):

acc_s = Q @ K[i]

scores_max_prev = scores_max

scores_max = max(acc_s, dim=1)

scores_scale = exp(scores_max_prev - scores_max)

acc_o *= scores_scale

acc_s = exp(acc_s - scores_max)

acc_o = acc_s @ V[i]

...

Here, acc_s represents the Q @ K result in each iteration with dimensions [block_M, block_N], while acc_o represents the current iteration’s output with dimensions [block_M, dim]. Both acc_s and acc_o need to be stored in registers to reduce latency.

Compared to traditional attention operators like MHA (Multi-Headed Attention) or GQA (Grouped Query Attention), a major challenge in optimizing MLA is its large head dimensions - query and key have head dimensions of 576 (512 + 64), while value has a head dimension of 512. This raises a significant issue: acc_o becomes too large, and with insufficient threads (e.g., 128 threads), register spilling occurs, severely impacting performance.

This raises the question of how to partition the matrix multiplication operation. On the Hopper architecture, most computation kernels use wgmma.mma_async instructions for optimal performance. The wgmma.mma_async instruction organizes 4 warps (128 threads) into a warpgroup for collective MMA operations. However, wgmma.mma_async instructions require a minimum M dimension of 64. This means each warpgroup’s minimum M dimension can only be reduced to 64, but a tile size of 64*512 is too large for a single warpgroup, leading to register spilling.

Therefore, our only option is to partition acc_o along the dim dimension, with two warpgroups computing the left and right part of acc_o respectively. However, this introduces another challenge: both warpgroups require the complete acc_s result as input.

Our solution is to have each warpgroup compute half of acc_s during Q @ K computation, then obtain the other half computed by the other warpgroup through shared memory.

Layout Inference¶

While the above process may seem complex, but don’t worry - TileLang will handle all these intricacies for you.

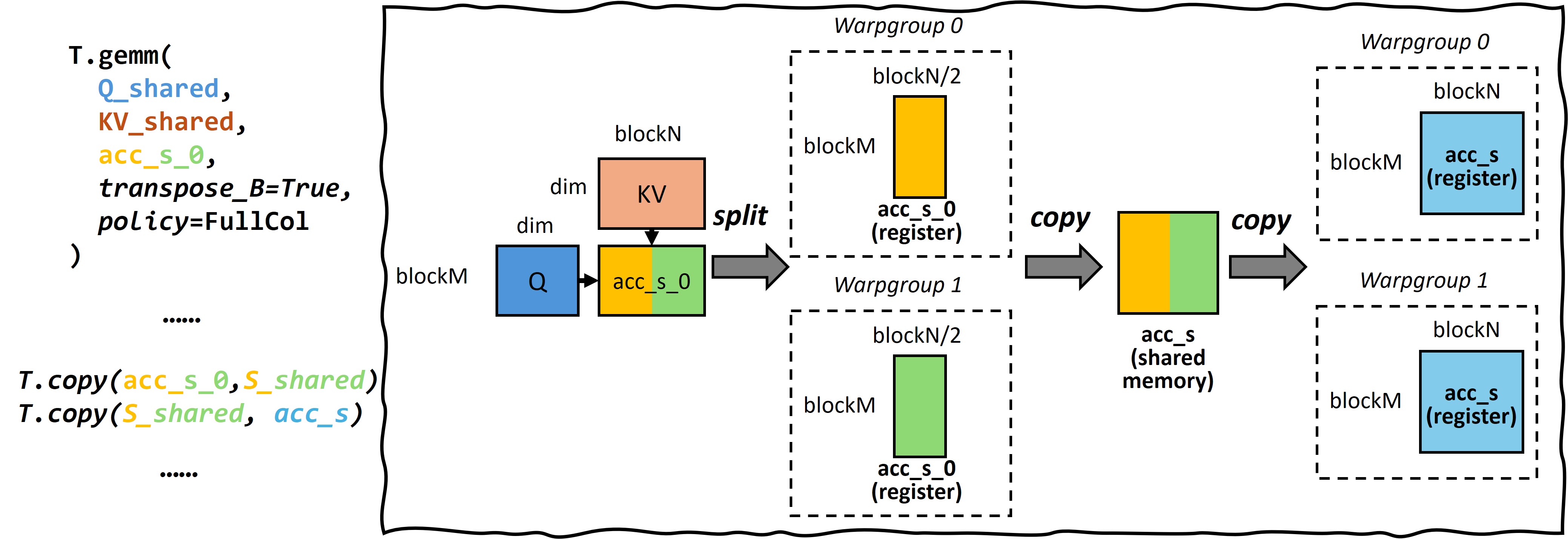

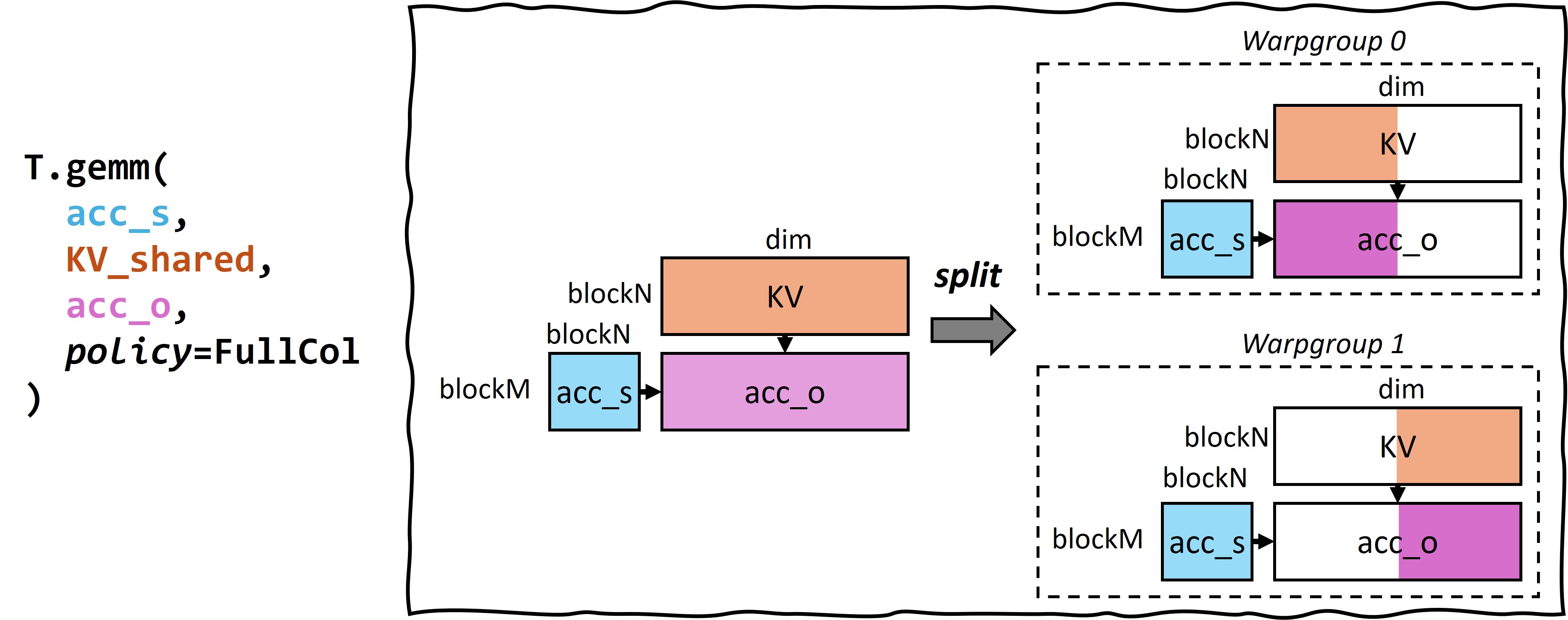

Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the frontend TileLang script and its corresponding execution plan for MLA. Here, T.gemm represents matrix multiplication operations, transpose_B=True indicates transposition of matrix B, and policy=FullCol specifies that each warpgroup computes one column (e.g., split the result matrix in vertical dimension). T.copy represents buffer-to-buffer copying operations.

Figure 3: Buffer shapes in Q @ K¶

Figure 4: Buffer shapes in acc_s @ V¶

The mapping from TileLang frontend code to execution plan is accomplished through Layout Inference. Layout inference is a core optimization technique in TileLang. It automatically deduces the required buffer shapes and optimal layouts based on Tile-Operators (like T.gemm, T.copy, etc.), then generates the corresponding code. Here, we demonstrate a concrete example of buffer shape inference in MLA.

For instance, when computing Q @ K, TileLang infers that each warpgroup’s acc_s_0 shape should be [blockM, blockN / 2] based on the policy=FullCol annotation in T.gemm. Since this is followed by an acc_s @ V operation with policy=FullCol, which requires each warpgroup to have the complete acc_s result, TileLang deduces that acc_s’s shape at this point should be [blockM, blockN]. Consequently, TileLang can continue the inference process forward, determining that both S_shared and acc_s in T.copy(S_shared, acc_s) should have shapes of [blockM, blockN].

It’s worth noting that our scheduling approach differs from FlashMLA’s implementation strategy. In FlashMLA, Q @ K is assigned to a single warpgroup, while the acc_o partitioning scheme remains consistent with ours. Nevertheless, our scheduling approach still achieves comparable performance.

Threadblock Swizzling¶

Threadblock swizzling is a common performance optimization technique in GPU kernel optimization. In GPU architecture, the L2 cache is a high-speed cache shared among multiple SMs (Streaming Multiprocessors). Threadblock swizzling optimizes data access patterns by remapping the scheduling order of threadblocks, thereby improving L2 cache hit rates. Traditional scheduling typically executes threadblocks in the natural order of the grid, which can lead to non-contiguous data access patterns between adjacent threadblocks, resulting in inefficient utilization of cached data. The swizzle technique employs mathematical mapping methods (such as diagonal or interleaved mapping) to adjust the execution order of threadblocks, ensuring that consecutively scheduled threadblocks access adjacent or overlapping data regions.

In TileLang, threadblock swizzling optimization can be implemented with just a single line of Python code:

T.use_swizzle(panel_size: int, order: str = "row")

Here, panel_size specifies the width of the swizzled threadblock group, and order determines the swizzling pattern, which can be either “row” or “col”.

Warp-Specialization¶

The Hopper architecture commonly employs warp specialization for performance optimization. A typical approach is to designate one warpgroup as a producer that handles data movement using TMA (Tensor Memory Accelerator), while the remaining warpgroups serve as consumers performing computations. However, this programming pattern is complex, requiring developers to manually manage the execution logic for producers and consumers, including synchronization through the mbarrier objects.

In TileLang, users are completely shielded from these implementation details. The frontend script is automatically transformed into a warp-specialized form, where TileLang handles all producer-consumer synchronization automatically, enabling efficient computation.

Pipeline¶

Pipeline is a technique used to improve memory access efficiency by overlapping memory access and computation. In TileLang, pipeline can be implemented through the T.pipelined annotation:

T.pipelined(range: int, stage: int)

Here, range specifies the range of the pipeline, and stage specifies the stage of the pipeline. Multi-stage pipelining enables overlapping of computation and memory access, which can significantly improve performance for memory-intensive operators. However, setting a higher number of stages consumes more shared memory resources, so the optimal configuration needs to be determined based on specific use cases.

Split-KV¶

We have also implemented Split-KV optimization similar to FlashDecoding. Specifically, when the batch size is small, parallel SM resources cannot be fully utilized due to low parallelism. In such cases, we can split the kv_ctx dimension across multiple SMs for parallel computation and then merge the results.

In our implementation, we have developed both split and combine kernels, allowing users to control the split size through a num_split parameter.

🚀 On AMD MI300X Accelerators¶

Following our previous demonstration of high-performance FlashMLA implementation on NVIDIA Hopper architectures using TileLang, this work presents an optimized implementation for AMD MI300X accelerators. We examine architectural differences and corresponding optimization strategies between these platforms.

Architectural Considerations and Optimization Strategies¶

Key implementation differences between Hopper and MI300X architectures include:

Instruction Set Variations: The MI300X architecture eliminates the need for explicit Tensor Memory Access (TMA) instructions and warp specialization, which are automatically handled by the compiler on Hopper architectures, resulting in identical source code manifestations.

Shared Memory Constraints: With 64KB of shared memory compared to Hopper’s 228KB, MI300X implementations require careful memory management. Our optimization strategy includes:

Reducing software pipeline stages

Register-based caching of Q matrices instead of shared memory utilization:

# Original shared memory allocation Q_shared = T.alloc_shared([block_H, dim], dtype) Q_pe_shared = T.alloc_shared([block_H, pe_dim], dtype) # Optimized register allocation Q_local = T.alloc_fragment([block_H, dim], dtype) Q_pe_local = T.alloc_fragment([block_H, pe_dim], dtype)

Tile Size Flexibility: The absence of WGMMA instructions on MI300X permits more flexible tile size selection, removing the requirement for block_m to be multiples of 64.

Memory Bank Conflict Swizzling: MI300x has different memory bank conflict rules compared to NVIDIA, so we need to use different swizzling strategies. This is also automatically handled by TileLang, resulting in no visible differences in the code.

Performance Evaluation¶

We conducted comparative performance analysis across multiple frameworks using float16 precision with batch sizes 64 and 128. The experimental results demonstrate:

Notably, TileLang achieves performance parity with hand-optimized assembly kernels (aiter-asm) in most test cases, while significantly outperforming both Triton (1.98×) and PyTorch (3.76×) implementations. This performance is achieved through a concise 80-line Python implementation, demonstrating TileLang’s efficiency and programmability advantages.

Future Optimization Opportunities¶

Memory Bank Conflict Mitigation: Current implementations primarily address bank conflicts in NT layouts through TileLang’s automatic optimization. Further investigation of swizzling techniques for alternative memory layouts remains an open research direction.

Dimension Parallelization: For large MLA dimensions (e.g., 576 elements), we propose investigating head dimension partitioning strategies to:

Reduce shared memory pressure

Improve compute-to-memory access ratios

Enhance parallelism through dimension-wise task distribution